Camille feeds London's bistro dream

A new French restaurant is wowing critics: but why is the idea of the perfect Parisian bistro so iconic for us? Plus: what I've been drinking this week

CAMILLE has opened in London’s Borough market to rave reviews: as Jimi Famurewa of the Evening Standard had it, “a supremely creative and confident new-wave bistro.” It has an enviable London foodie pedigree, brainchild as it is of Clare Lattin and Tom Hill of Soho’s Ducksoup, with its chef Elliot Hashtroudi an alumnus of St John.

And this is indeed superbly executed modern French food. “Biarritz-style” fresh sardines were meaty and fragrant; white asparagus with prawns and a prawn-head Hollandaise was perfectly judged. The shallot tarte tatin was chunky and unctuous; langoustine cassoulet unusual and delicious. And the butterflied gurnard was the most spectacular presentation I’ve seen of this modest fish, with irresistible stacks of potato pavé. We drank Beatrice and Pascal Lambert’s Chinon Rouge 2022, a pure and lovely expression of this classic Loire red.

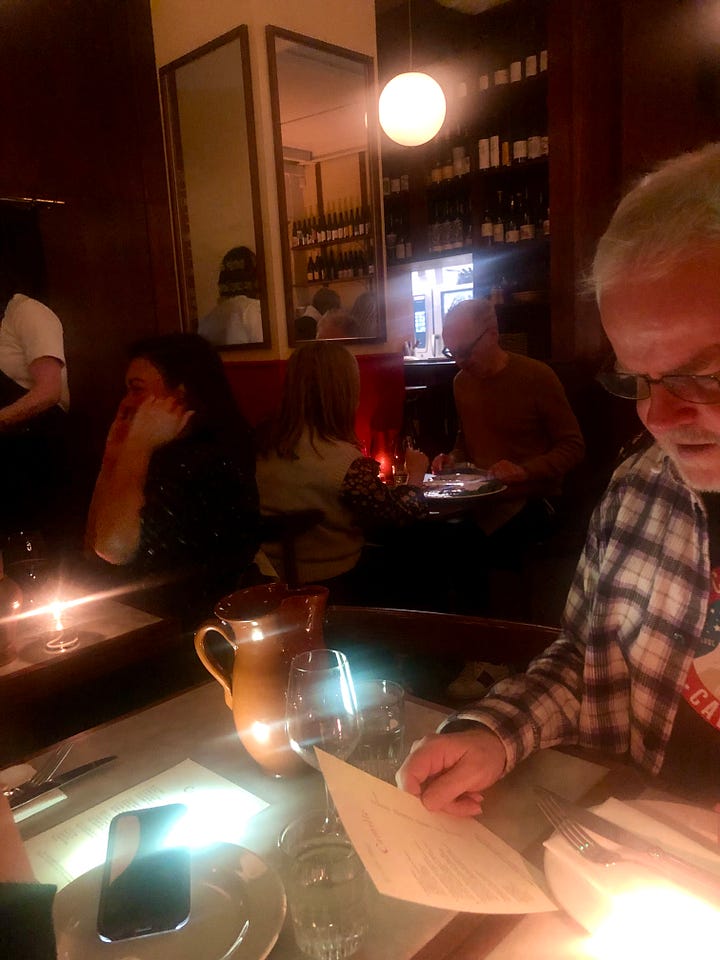

But not only is the food French, “a reflection of imagined jaunts through regional France”, as Camille’s website has it. The simple, understated décor – mirrors, dark-red wood panelling, simple dark-wood furniture, a chalkboard of specials – makes this an unashamed pastiche of that most French of culinary icons, the bistro. As the FT’s Tim Hayward put it, Camille is “a comfortable workers’ caff you might dream of finding on the edge of a Parisian fruit market”.

In fact, it isn’t even the most stereotypically Parisian bistro in London. That award perhaps goes to nearby Casse-Croûte, which is complete with French booze ads, Gallic staff smiling “Très bien, monsieur”, and decked out with the bistro’s most crucial signifier, red-and-white checked tablecloths. It should also be said that the hearty food – pigs trotter in filo with sauce tartare, endive salad with Roquefort and walnuts, and more – is very good, if somewhat less daring than that at Camille.

Time Out’s reviewer left the latter “full, tipsy and dreaming for Paris”. It’s hard to imagine British reviewers making a similar comparison with any other cuisine: no other culinary icon exerts quite the same influence on the British – or American – imagination as the humble French bistro. Why should that be?

To many anglophones, the bistro seems the distillation of Frenchness – and one that you can immerse yourself in without actually travelling to France. Perhaps its appeal is as a place where the cooking is unpretentious yet authentic, pretension in culinary matters being a particular source of suspicion to Brits.

Yet like any cultural phenomenon, the bistro was the product of a particular era and place, and has changed over time. Bistro (or bistrot) entered the printed French language in 1884, though its origins are disputed. But the establishments it described were products of a new market hungry for cheap eating places, the emergent late-nineteenth-century urban classes in cities like Paris and Lyons.

And while bistro cooking is traditionally about homely, rustic dishes, by the late nineteenth century French cooking had already been profoundly influenced by the great chef Marie-Antoine Carȇme. His bible, L’Art de la Cuisine Française au Dix-Neuvième Siècle (1854) was still taught to French chefs at the start of the twentieth century, when it was updated his celebrated successor, Auguste Escoffier. Without them, many bistro classics would not exist – anything involving Hollandaise or velouté sauce, for instance, both among the “mother sauces” invented by Carȇme and tweaked by Escoffier.

However, the archetype of the bistro in English and American minds dates to the mid twentieth century. Google’s Ngram tool suggests “bistro” was first used in English in the early 1920s. And when American writers such as A.J. Liebling and Joseph Wechsberg memorialised bistro culture in the New Yorker and elsewhere in the 1950s, it was primarily the Paris of the twenties they were describing.

In Blue Trout and Black Truffles (1954) Wechsberg recalled of his neighbourhood bistro in Pigalle in 1926, “Young couples would hold hands as they ate a delicious raie au beurre noir or a vol-au-vent. Between bites of food they would exchange passionate kisses.” What Anglo-Saxon could resist such Gallic romance?

Likewise Ernest Hemingway, but in his telegraphic prose, the bistro’s aura is made yet more alluring by its simplicity. In A Moveable Feast (1964), Hemingway describes eating potato salad with beer at Brasserie Lipp in 1926: “The beer was very cold and wonderful to drink. The pommes a l’huile were firm and marinated and the olive oil delicious. I ground black pepper over the potatoes and moistened the bread in the olive oil.”

Britain was probably more heavily influenced in the 1950s and 60s by Elizabeth David, post-war prophet of unpretentious French food to the English middle classes. And the new food guides of the 1950s – the Good Food Guide and Egon Ronay – kept Britain’s nascent food culture focussed on the French lodestar.

Yet by 1980, David was decrying the deterioration in French restaurant cooking, not least in roadside joints where “the food [is] squalid and the wine lethal.” By then, classic Paris bistros such as L’Ami Louis and Le Procope were either becoming expensive or else resting on the laurels.

So it was that in the 1990s, Paris’s jaded restaurant scene spawned the bistronomie trend, led by chefs like Yves Camdeborde. Talented young chefs took advantage of lower rents than in London to revamp spaces often in cheaper parts of town such as Belleville. The aesthetic is fresh, seasonal takes on classics, usually with far less stiff service or formal presentation than in the old guard – and at lower prices.

That trend has intensified in the past decade with the so-called neo-bistro movement. At somewhere like Au Passage, for example, the furniture is scuffed, some of the plates mismatched, and the staff tattooed. Natural wines feature heavily. But the food is exciting.

In this respect, Camille is both a nod to past and current incarnations of the bistro. It’s French enough to charm us, but with food sophisticated enough to impress the most blasé metropolitan palates. The dark days of the 1970s in London dining are long gone: we don’t need to cross the channel to find the culinary cutting edge. Still, it’s nice to re-experience the Gallic icon which still so influences our ideal of convivial dining.

What I’ve been drinking this week

Cristo del Humilladero Gre2 2019, Vino de Madrid - the rugged, high Sierra de Gredos area just west of Madrid has attracted a fair bit of hype in recent years for its fine red Garnachas, but I think the excitement is justified. Light, fine, pure and focussed, almost like a Pinot Noir rather than a Garnacha (Cave Bristol, Vin a Go Go, Shekleton Wines and elsewhere, from £14.45.)

Le Clos du Caillou “Les Quartz” 2020, Côtes-du-Rhône - a Châteauneuf-du-Pape in all but name - it’s excluded from the appellation by a historical quirk - this brims with spicy black Grenache fruit (plus a little Syrah.) Dark, deep and long, but while powerful, it has finesse - it doesn’t really taste like its 15 per cent alcohol (Authentique Wines, £26 - glad I got mine from the Wine Society en primeur at £15.70/bottle!)

Bodega Atamisque “Serbal” Malbec 2022, Mendoza - from the Tupungato area of the increasingly exciting Uco Valley, this is beautiful: savoury, herbal notes, perfectly balanced and not at all heavy (De Burgh Wine Merchants, £15.49; The Secret Cellar has the 2021, £16.50.)