Farewell to the father of modern Greek wine

The death of Yiannis Boutaris robs Greece of one of its most influential, charismatic winemakers. Plus: what else (apart from Xinomavro) I've been drinking lately

Few wine regions have a history as bound up with a single personality as northern Greece’s Naoussa does with Greek winemaking legend Yiannis Boutaris, who has died aged 82. But Boutaris was more than just a winemaker: he was also a businessman of great acumen and a courageous politician.

It is hard to believe today but Xinomavro, Greece’s greatest red grape and one garnering critical plaudits globally for a decade, had dwindled close to extinction in the mid-1960s. The Naoussa vineyards were ravaged by phylloxera and rural poverty. This was when the 23 year-old Boutaris joined his father in the family wine business, set up by his grandfather in 1879. The Boutari company were a major player in the Greek wine industry – and a big ouzo producer – and the Boutaris were a prosperous dynasty. But the industry remained backward, held back by low investment and low quality, with almost all wine produced for domestic consumption.

Boutaris, however, believed in Xinomavro, the main local red grape, now much-praised for its Nebbiolo-like qualities of acidity, bright fruit and earthy tannins. He soon set about planting the first single-varietal Xinomavro vineyards. And in 1970, he planted more than 40 hectares of Xinomavro on the eastern foothills of Mt Vermion, in Naoussa.

It was a radical move for the time: then, the local vineyards all made field blends of different red and white grapes. Local growers mostly sold their fruit rather than making wine. But Boutaris bolstered their confidence by working with others pushing for official recognition of the region, leading to the establishment of the three of Greece’s four recognised Xinomavro appellations: Naoussa (set up 1971), Amyndeon (1972) and Goumenissa (1979).

“Assyrtiko from Santorini was the first Greek variety that made it [internationally]’,” says Markus Stolz, an Athens-based importer of Greek wine to the US. “For me it was only natural that Xinomavro would follow, as it is so unique, ageworthy and well priced.”

Not that Boutaris shunned international grape varieties: in the 1980s and 90s he also planted Chardonnay, Syrah, Merlot and others. Many Greek producers did the same, in the hope that it would make their wines more exportable. But there was a growing realisation from the late 1990s that the country’s indigenous grapes were unique, with the potential to make serious fine wine. And since that era there has also been a steadily increasing emphasis on quality, in an industry which had historically been more focussed on quantity.

Boutaris also pioneered this approach in the nearby Amyndeon region. In the 1980s he planted 20 hectares of white varieties – Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc and later Greek grapes including Assyrtiko, Malagousia and Roditis – on the highlands to the west of Mt Vermion. Though the area had a long winemaking history, it wasn’t regarded as promising at the time: it was a poor area, on a high-altitude plateau (over 550 metres) that makes it the coldest winegrowing area of Greece. Today its wines’ quality is well established and it is home to a new generation of wineries, such as Alpha Estate.

And in addition to all that, Boutaris grew the wider family business, expanding to six wineries throughout Greece. And from 1994, the company also acquired a major brewery, launching popular Greek brew Mythos in 1997.

Yet Boutaris was becoming restless. In 1996, he parted company with the family firm, buying an old winery in the Naoussa village of Agios Panteleimon. The following year, it became the home of his new venture, Kir-Yianni (“Sir John”). The honorific, he told the Athinea news website in a 2021 interview, “was a recognition I received from the winegrowers in Naoussa when my grandfather died and I took over. So, from being Giannakis [“little John”] for a few years, I became Kyr Yiannis overnight." This became the name for his new venture because, “I didn’t want to use my name for my own wines. I didn’t think it was right to create confusion and competition with Boutari.”

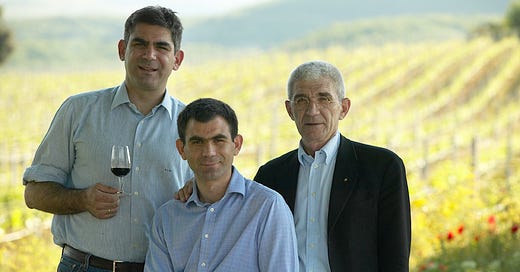

Xinomavro remained at the centre of Boutaris’s ambitions at Kir-Yianni, even though he and his sons, Stelios and Mihalis, also planted a number of international varietals. They began experimenting with different Xinomavro clones and different vineyard sites and soils, segmenting the estate into 42 different blocks from which to draw research data. As he told Athinea, “What is a good vineyard? The one you control. Where you know its roots and where you can guarantee its quality.” They planted a further 28 hectares with Xinomavro and other grapes; Xinomavro remains half of the estate’s plantings today.

I never met Yiannis Boutaris: by the time I visited Kir-Yianni in 2012, he had long since handed over control of the estate to Stelios. It had turned into a big operation, though they kept older traditions going: that September, during harvest, I watched grape-pickers gather around a makeshift altar in the winery as a chubby Greek Orthodox priest dipped a bunch of basil in holy water to sprinkle us in blessing. Today, Kir-Yianni produces over a million bottles a year. And in 2020 they also took over Domaine Sigalas, one of Santorini’s leading estates, well known for its fine Assyrtiko – of which Yiannis Boutaris was an early admirer.

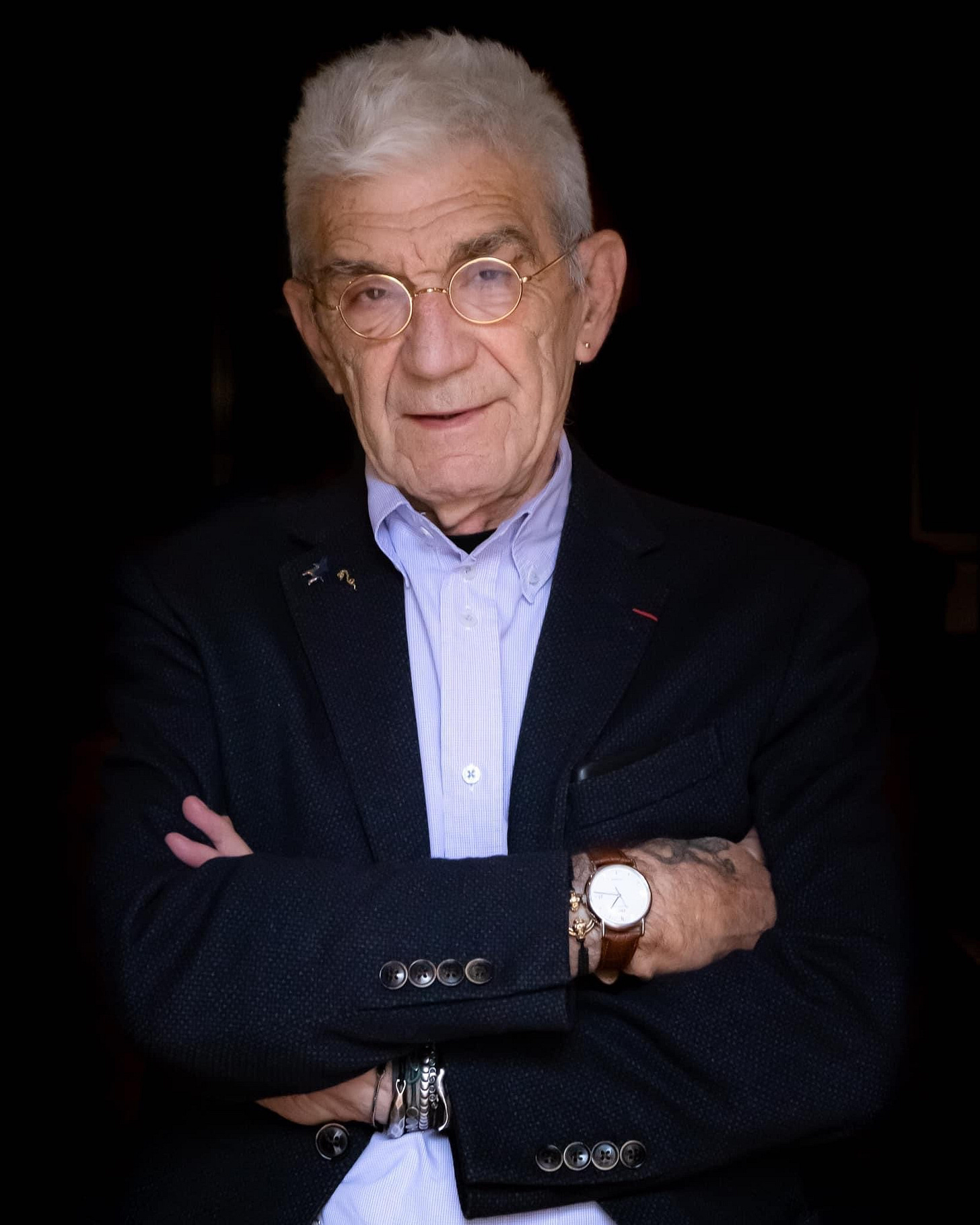

But while Stelios ran the business, Boutaris père, in typically idiosyncratic style – he sported an earring and a number of tattoos – had gone into politics. Long an environmental campaigner, in 1992 he had founded leading Greek environmental NGO Arcturos, focussed on protecting wildlife, natural habitats and biodiversity. And in 2003 he was elected to the town council of Thessaloniki, Greece’s second city and his place of birth.

Then in 2010 he narrowly ousted the spectacularly corrupt incumbent, Vasilis Papageorgopoulos of the right-wing New Democracy party, to become the city’s Mayor. Yet despite his lifelong progressivism and support from socialists PASOK, he never aligned with any party himself, always the maverick.

As Mayor from 2011-2019, he regularly enraged the Greek far Right. A supporter of gay rights, the city saw its first Pride parade under his mayoralty. He encouraged Turkish tourism to this, the city of Kemal Atatürk’s birth. At his re-election swearing-in ceremony in 2014, in protest at the presence of a neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party councillor, he wore a World War II-era Star of David “Jude” badge, like those the Germans made Jews wear during their occupation, 1941-44, (they sent 56,000 Thessaloniki Jews to Auschwitz: the city was home to by far Greece’s biggest Jewish community.)

And in May 2018 he was beaten up by ultra-nationalist thugs; nine people including a serving police officer were finally convicted last year of the attack on the then-75 year-old Mayor. Asked for his reaction to the attack, he said, “It made me think about how I could expose these thugs from my position. It didn’t scare me at all.” He stood down as mayor in 2019. His health had been failing in recent years; he was a recovered alcoholic and lifelong smoker.

Today Stelios Boutaris is still at the helm of Kir-Yianni, and its wines remain impressive. In line with its founder’s green principles, Kir Yianni is also a leader in sustainability in the Greek wine industry. In the vineyard, they plant cover crops between vine rows and use pomace (waste grape skins and stalks) for fertiliser. In the winery, around a third of their electricity is generated by photovoltaic panels on the roof; they use LED lighting and heat pumps; they recycle both the water used in the winery and other waste. They also plan to reduce the weight of the bottles they use, by far the biggest contributor to wine businesses’ carbon footprint.

Greece’s wine industry today has changed out of all recognition to the trade that Boutaris joined in 1965. Incredibly, Greek wine producers have recovered from both the financial crisis of 2008 and after, which struck Greece far harder than anywhere else in Europe, and the Covid-19 pandemic. The country’s wines are enjoyed in wine bars and fancy restaurants across the world. And if one single person can take credit for that transformation, it is Yiannis Boutaris.

Yiannis Boutaris, 13/6/1942 - 9/11/2024. Ας είναι ελαφρύ το χώμα που θα τον σκεπάσει.

Four Xinomavros to try

Kir-Yianni “Ramnista” Xinomavro 2019, Naoussa – Kir-Yianni’s single-vineyard Naoussa is a dark, powerful Xinomavro in a plusher, more modern style than some, black and bright cherry fruit still nicely balanced with acidity (Vinum, Shelved Wine and elsewhere, from £23.70.)

Thymiopoulos Jeunes Vignes 2022, Naoussa – over the past few years, Apostolos Thymiopoulos has established himself as one of Greece’s foremost winemakers and perhaps its greatest current champion of Xinomavro. This boasts true varietal character at a great price – one of my go-to reds (The Wine Society, Dark Sea Wine, The General Wine Co, from £13.50.)

Karanika Xinomavro old vines 2019, PDO Amyndeon – Laurens Hartman cultivates Xinomavro regeneratively, rejecting organic or biodynamic certification (“I hate following rules,” he told me earlier this month) in favour of viticulture which concentrates on soil health and putting nutrients back into the soil via grape pomace, straw and mule dung. This brims with pure, sweet fruit, elegant and finely balanced with the grape’s trademark acidity and tannins (Maltby & Greek, £23.50.)

Foundi “Naoussea” 2018, Naoussa – classic Xinomavro in a more traditional style, with firmer tannins that need a little time to soften. More savoury than some, with tomato-leaf and sour-cherry flavours: needs food (The Good Wine Shop, Dark Sea Wine and elsewhere, from £26.25.)

What else I’ve been drinking lately

Dupuis Baker Ranch Syrah 2018, Anderson Valley - from up north in Mendocino County, California, the cool Anderson Valley produces some distinctly European-style wines like this organic Syrah, at only 13 per cent alcohol. Rhône-style peppery red fruit but deceptively powerful and heady. A fascinating Californian Syrah, and more affordable while on offer (Roberson, currently reduced to £29.09.)

Natasha Williams “Lelie Van Saron” Syrah 2021, Upper Hemel-en-Aarde Valley - there isn’t any particular reason why I’ve been consuming multiple New World, Rhône-style Syrahs recently except, well, that’s my bag. For my money the Hemel-en-Aarde valley is producing some of South Africa’s most serious wines these days, like this one boasting pure, peppery bramble fruit and fine tannins - lovely (The Wine Society, £22.)

Alfredo Maestro “Viña Almate” 2022, Ribera del Duero - Maestro is a natural winemaker in Spain’s high-quality Ribera del Duero region. I liked this for its freshness and balance, full of bright Tempranillo fruit with nice, juicy acidity (Hay Wines, Parched, Buon Vino, from £16.99; also by glass/bottle in various London restaurants including Lasdun, at the National Theatre, where I drank it.)

What a hero, I didn't know about him, a truly exceptional human being.

Great story, thank you