Finding wine's sweet spot

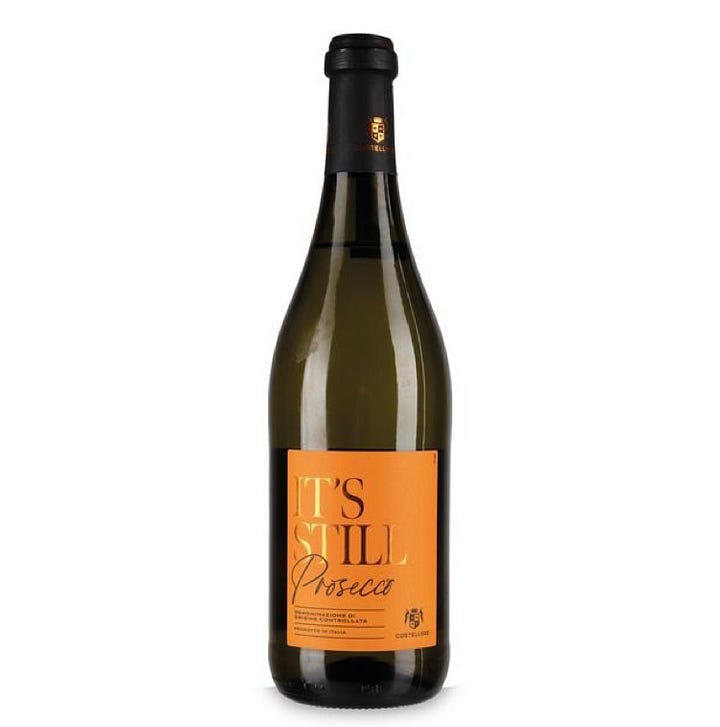

Aldi's new still Prosecco highlights a little-noticed feature of many mass-market wines: their high sugar levels. Plus: what I've been drinking this week

I suppose it’s part of capitalism’s warped genius to invent new things that we didn’t realise we needed. But there are surely limits. Aldi’s new still Prosecco (£5.99) is a case in point.

Removing the only thing that makes Prosecco vaguely interesting – the bubbles – may be a step too far even for industrial megaplonk. I haven’t tried it yet, though it seems unreasonable to expect the wine to taste dramatically different to the rest of the anodyne oceans pumped out by the wine factories of north-eastern Italy. Nevertheless, I’m realistic enough about the influence of wine writers on public tastes (close to zero) to realise that, on the contrary, bubble-free Prosecco might in fact succeed. And this set me wondering afresh about the British public’s tastes – and mine.

In fact, according to the Prosecco’s Consorzio (professional body), still wine does make up 0.1 per cent of the area’s 700 million-odd bottles a year production. Aldi’s is made by industry behemoth Italian Wine Brands, which produces 190 million bottles of wine annually in various parts of Italy. And it has seven grammes per litre of residual sugar – firmly in “off dry” territory, on a par with public favourites such as Barefoot Pinot Grigio (8g/litre).

Because one of the secrets of Prosecco’s astonishing success – it was almost unknown in the UK 25 years ago, but now we import around 120 million bottles a year – is its relative sweetness. Residual sugar is the sugar left in the wine at the end of fermentation, though in most sparkling wines a small amount of sugar is added at bottling as well. Like Champagne, to be classified as “Brut”, Prosecco must be bottled with under 12g/litre of sugar. But most big Prosecco brands in the UK are in fact the next-sweetest category up, confusingly termed “extra dry”, such as Valdo (15 g/litre), La Marca and Freixenet Prosecco (both 17g/litre). That’s not dry at all: it’s pretty sweet.

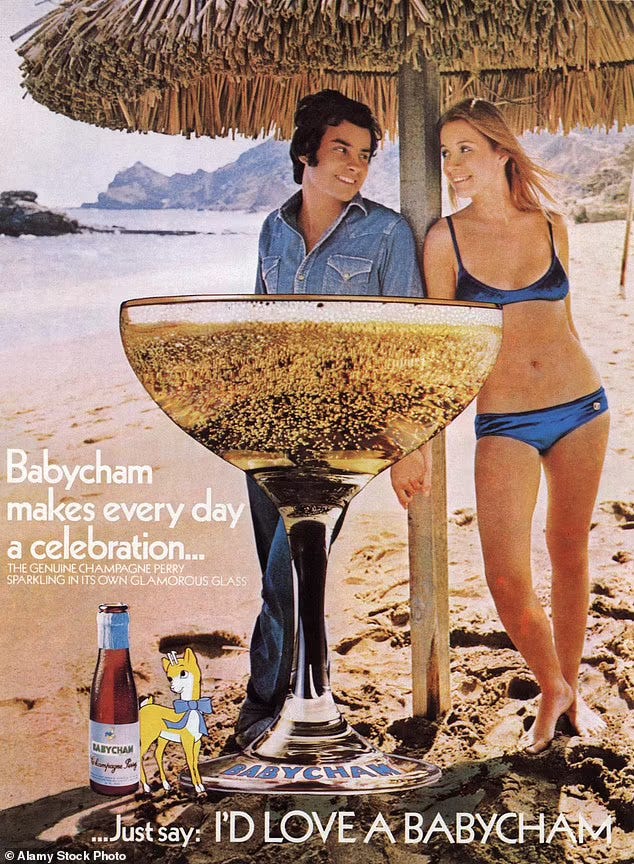

Maybe the success of the formula shouldn’t be so surprising. Prosecco has followed where Babycham showed the way. The sparkling, sweetish perry drink, devised by a family of enterprising Westcountry cider makers in 1953, was wildly popular in the 1960s and 70s: at its peak in 1977, it sold 144 million (small) bottles a year. It was also the first alcoholic drink ever marketed specifically to women: prior to that, the only acceptable order in a pub for women was port and lemon. Half a century on, this was a lesson well learnt by Prosecco.

Sweetness sold well in the 1970s and 80s too, with the success of brands such as Blue Nun (30g/litre residual sugar), Mateus rosé (15g/litre – perhaps even more back then), and Black Tower (a mere 8g/litre). And while the conventional wisdom is that from the 1980s, the public’s tastes shifted towards drier whites, I don’t think it’s as simple as that. As wine writer Robert Joseph points out, until the early 80s, people had a choice between either the sweet whites or anodyne ones such as Frascati, Muscadet and (industrial) Soave. But then, he says, “the Australian and New Zealand wine carved a path between sweet and flavourless”, exploiting previously undreamt-of fruit while also often having a few grammes of residual sugar.

In fact even by the 1970s, the British wine-buying public was changing, with the growing popularity of wine bars and more foreign travel. Yet red Bordeaux was tannic and lean to most people’s tastes (and it actually was pretty tannic and lean in those days, before either climate change or the revolution in winemaking.) So how to get the public to drink red wine? David Gluckman, the marketing guru who dreamt up Bailey’s Irish Cream, was also responsible, in 1974, for the launch of Le Piat d’Or.

In his aptly titled 2022 memoir, That sh*t will never sell!, he recalls, “We wanted a sweet, easy-drinking red wine without any of the punishment of tannin which characterised many French wines at the time. We chose an unorthodox method to achieve that aim. Our product ‘template’ was to use the Liebfraumilch Blue Nun liquid and colour it red using proprietary food colouring.” That was the “wine” preferred by the focus groups he tested it on. So he went to a French manufacturer and asked them to come up with just that taste. The result – with 10.5g/litre residual sugar, “dry without the edge” as the ads had it – was one of the biggest-selling wines of the 80s.

And to this day, high residual sugar is a feature of many, though not all, mass-market reds in the UK. For makers of these kind of industrially made wines, adding a little grape concentrate to give more sweetness is not uncommon. I was reminded of this at Majestic’s spring press tasting earlier this month by a series of reds on the sweeter side, such as Rimini Rosso (7g/litre), Portuguese red Behind Closed Doors (7.6g/litre), and Chilean The Traitor Red Blend (9g/litre). But those are modest compared to some of the big brands: Majestic’s own big-selling Spanish red, The Guv’Nor has 18g/litre, as does McGuigan Black Label Red and Hardy’s Crest Cabernet-Shiraz (both 18g/litre). And let’s not even think about Jam Shed Shiraz (31.8g/litre) or Yellow Tail Jammy Red Roo (38g/litre – no, really, please let’s not think about them.)

Of course someone like me can find plenty of technical grounds on which to criticise these wines: though they’re rarely faulty as such, they’re very simple, out of balance, confected – and over-sweet. But winemakers can, to a degree, conceal high sugar with higher alcohol: anything over 3-4g/litre jumps out at me, but I’d probably be less likely to guess the residual sugar level in a big, powerful, fruity red (even though I still wouldn’t much like it.) Acidity plays a role too in our perception of sweetness – and that’s easy for industrial wineries to tinker with.

It may be that I have a particularly un-sweet tooth: I rarely eat desserts. At a big Lambrusco tasting in London last year, where many of these traditionally sweeter Italian reds had 8g/litre sugar or more, I was left nonplussed by serious critics raving about the wines and how well they go with the local food: I thought they were grim. People’s tolerance for sugar does vary: Americans’ is notoriously high. Indeed in the early twentieth century, some champagne houses made a sweeter bottling for the US market labelled “gout américain”, with 110g/litre-plus of sugar (for comparison, Coca‑Cola Original has 106g/litre.)

Nevertheless, individual palates aside, most wine professionals do dismiss these sweeter reds – and big-brand off-dry whites too – as rubbish. Or as the inimitable Tom Gilbey said of 19 Crimes Malbec last week, “that tastes like someone’s had a dump in my windscreen washer”. Yet they sell by the tanker-load – or to be exact, for 19 Crimes, 20 million bottles a year in the UK.

“There’s a yawning gap between the way wine critics think wine should taste and the way a large number of people who drink wine think it should taste,” says Joseph. “Are we like the film critics that only want to see the subtitled foreign movies and not Marvel?” Henry Jeffreys concluded something similar recently.

I don’t think it’s because drinkers have rubbish palates: indeed one of the things I always tell people when I conduct tastings is precisely that you don’t need a special palate to be able tell different wines apart. You just need a bit of knowledge and experience.

Which most wine drinkers don’t have. I’ve made the comparison before between people knocking back wine that they know isn’t very good with my own attitude to lager: both do the job. Part of this is about marketing. For all the Blossom Hills and Yellow Tails, wine is a notoriously fractured market compared to most alcoholic drinks. Beers and spirits are completely dominated by brands, and their makers are very good at selling them. Last summer I visited the Cointreau factory in Angers, in the Loire: the museum there tells a fascinating story about the sophistication of French booze marketing a century ago or more. Wine still hasn’t caught up. And that inevitably influences people’s choices.

So you also need some curiosity about what you’re drinking – and about what else is out there – to break out of the supermarket mainstream. If you’re reading this, then pretty much by definition, you’ve broken out of it. And if you’re still tempted by bubble-free Prosecco, don’t say you weren’t warned.

What I’ve been drinking this week

I’m hunkered down writing my book and turning to comfort wines just now:

Château Sainte Eulalie “Le Printemps d’Eulalie” rosé 2024, Minervois – the sun was out at the weekend, so out came my go-to rosé: fresh, clean, lots of red fruit – lovely on its own but with a bit of weight to stand up to food too (The Wine Society, £10.50.)

The Society’s Generation Series Hemispheres White 2023 – a highly unusual white blend of Marsanne and Viognier grown by Chapoutier in the northern Rhône with some of the same two grapes grown in Victoria state, Australia. It was blended and bottled in the UK (you could probably be arrested at the border if you tried taking a bottle of such heresy to France.) Fresh, bright, fruity – and as you’d expect, a little hard to place (currently on offer at £13.50, reduced from £16.50.)

Château Musar 2017, Bekaa Valley – once on a visit to Lebanon, the great Serge Hochar asked me whether I thought his wine was underpriced in the UK and if he could get away with charging a bit more. I told him yes. This may or may not be the reason, in part, why I can’t really afford it any more. Anyway, this classic is as brilliant as ever: ripe, spicy, earthy, utterly distinctive (widely available, from £43.)

Aldi is by far the largest wine retailer in Germany ( where I live ). The wines are mostly very cheap (average price 2.84 Euro / Litre and very modest). Yet Aldi is a very clever at marketing. There is always a Master of Wine or Master Sommelier willing to rate their wines highly and praise them in glowing terms. My friends rave about how incredible Aldi Champagne (at 17,99 Euro). Hard to believe, but Aldi is able to put Barolo, Brunello and Amarone on the shelf at comparably low prices around Christmas time. How can you resist)

This is a very nice piece (and thanks for the mention), but it glosses over the personal-taste element. Some people, as you acknowledge, have a much sweeter taste than others. I know wine lovers who adore Sauternes and wine lovers who are sniffy about anything sweeter than an Ultra-Brut fizz. And neither is 'wrong'.

It is likely that some of those experts who applauded the sweet Lambruscos that you disliked are simply genetically or culturally calibrated differently to you. They may enjoy the desserts that you prefer not to eat. I *get* this. I have friends with very different sweetness thresholds.

Of course, this does not mean that Aldi's still Prosecco is good (I haven't tasted it), but there's no reason why a version of that wine - A Glera that hasn't been through the Charmat process; an Italian equivalent of a Coteaux Champenois Chardonnay - should not be a nicely balanced off-dry wine that will please people who enjoy that style.

I don't drink Prosecco very often, but I am a senior judge at the annual 5 Stars competition in Verona at which we have to judge a lot of them. Some - not always the DOCGs - are first class, as are some of the sweeter Lambruscos