How we became a nation of pasta lovers

The BBC's famous 1957 April Fool on the spaghetti harvest is a reminder of how recently Britain's food has been transformed. Plus: what I've been drinking this week

APRIL 1 this week inevitably saw another outing on social media for the most glorious ever media April Fool. BBC Panorama’s 1957 spoof report on the Ticino spaghetti harvest was later dubbed by CNN "the biggest hoax that any reputable news establishment ever pulled".

As happy villagers pluck pasta from their “spaghetti trees”, BBC veteran Richard Dimbleby intones that “another reason why this may be a bumper year lies in the disappearance of the spaghetti weevil, the tiny creature whose depredations have caused much concern in the past.” The legendary broadcaster informs us that the surprisingly uniform length of the pasta strands “is the result of many years of patient endeavour by plant breeders”.

How many of the estimated eight million viewers were fooled? Certainly some: hundreds reportedly phoned in to ask how they could grow their own spaghetti. For the pasta was little known in the UK in the 1950s except for the tinned version in gloopy tomato sauce, launched by Heinz in 1926 (the company daringly brought out tinned hoops in 1969.)

It’s hard to imagine now: so many foods we today consider unremarkable were then rare or unknown. Forget ‘nduja, burrata or za’atar: even spaghetti was exotic. But from the perspective of 2024, the Panorama April Fool raises a serious question: what did English people actually eat in the 1950s? I assume they subsisted on meat-and-two-veg standards like pork chops and new potatoes, or sausages and mash. But every day? Even, say, students?

Macaroni cheese was a well-established British staple. Indeed the first recipe for it was published in 1769, from where it went to the American colonies: there is supposedly a hand-written favourite recipe for it by US founding father Thomas Jefferson. I certainly ate plenty of it in my 1970s childhood: American “mac and cheese” was a good 40 years away from superfluous re-importation. But when my parents married in 1962, my mother’s go-to recipe book, Marguerite Patten’s Cookery in Colour (1961), featured a total of just three pasta recipes.

Two of these were “Creole macaroni” and “Spaghetti soufflé”, creations sadly lost to culinary history. The third was spaghetti Bolognese.

Pioneering English food writer Elizabeth David had published the first recipe for spaghetti Bolognese in her book Italian Food (1954). But it’s hard to believe that her anglicised recipe – actual Bolognese wouldn’t traditionally eat spaghetti with ragù – was especially popular with home cooks, not least because few British food shops sold any dried pasta except macaroni. Brits ate spaghetti primarily in Italian restaurants, growing in popularity in the 1960s: the first Pizza Express opened on Wardour St, Soho in 1965.

At least in Devon then, dried spaghetti could be found only in a delicatessen (never then called a “deli”) and in the traditional 50cm lengths, wrapped in a blue paper packet. This was the unwieldy ingredient with which my mother first made spaghetti Bolognese in the mid-1970s; we greeted it as a culinary adventure roughly on a par with me serving my children Mongolian hotpot with morsels of horse.

Yet by the time I was at university a decade later, not only were supermarkets selling today’s 30-cm packs of long pasta (in fact a 1950s invention of Italian manufacturers). “Spag bol” was becoming a student staple: Google’s Ngram tool suggests the term gained currency from the late 1980s.

Lasagne’s British rise was even more meteoric. I first tasted it in an Italian restaurant in Exeter circa 1978, its novelty amplified by the use of green pasta: it was thrilling. Within half a dozen years, it had become a provincial favourite: I remember a schoolfriend visiting me one summer in the mid-80s and him cooking lasagne, evidently one of his specialities. By then you could buy dried pasta sheets that theoretically needed no cooking prior to assembly – at least if you made you lasagne in the sloppy style already beloved of English pubs.

Just how far that style was from the Bolognese original was underlined to me during an early-80s family holiday in Emilia Romagna. At our hotel’s implausibly large lunches, the pasta course sometimes consisted of a neat square of lasagne. The whole focus was on the feather-light pasta sheets – at least eight layers of them, with only a smear of beef ragu between each.

I left Britain for graduate school in the US; by the time I moved back in 1995, English food seemed transformed. Not only was fresh pasta readily available in supermarkets; pasta machines were common too. By the time I had my own children in the 2000s, pasta shapes with supermarket pesto were the most basic of stand-by kids’ dinners (would any British parent have even known what it was in 1970?) And now I rolled my own pasta, and my lasagne became a family favourite.

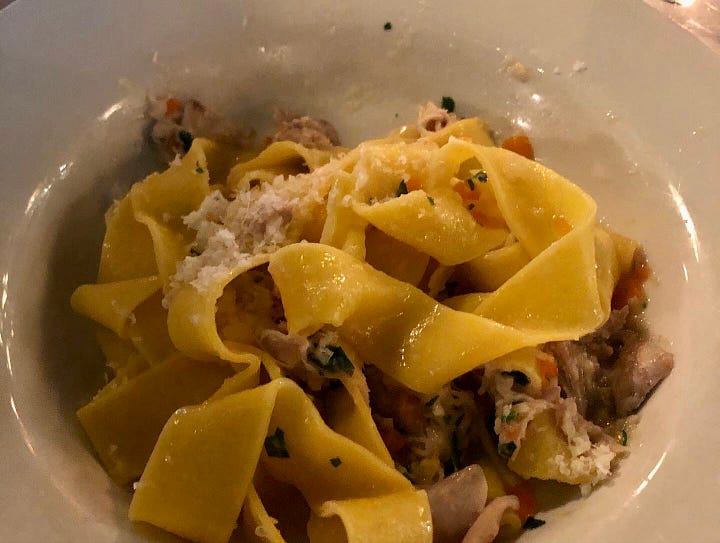

But while today Italian restaurants majoring on pasta are popular – as anyone who’s ever tried to get a table at Borough’s Padella can testify – outside of family, it’s not something I’d prepare except for the closest of friends. Britain’s headlong adoption of pasta has made it too ordinary for any meal where you want to show you’ve made an effort – never mind that making pasta is time consuming. If there are micro-waveable versions of a dish available in your local convenience store, how special can it be?

This is a shame, for pasta remains surely one of the most sublime and distinctive European culinary inventions. I will just have to up my game: I am shortly attending a ravioli-making course. Call it the acceleration of British foodie culture – but I’d rather be where we are now than in 1957, pondering whether to plant some spaghetti next to the runner beans.

What I’ve been drinking this week

The Society’s 150th Anniversary Gigondas, 2018 (The Wine Society, £29) – a highly unusual project, this is a blend of wines from five top producers in this key southern Rhône appellation - Boussières, La Gardette, Cazaux, Amadieu and Saint-Cosme. The result is an extremely fine Gigondas: pure, sweet fruit and perfect structure and balance. I drank this en magnum, brought to dinner by my generous friend David last weekend.

Jean Bouchard Mâcon-Lugny Les Charmes 2017 - Mâcon has long offered the best bargains for white Burgundy: this is a decent one from a reasonable négociant. Crisp and fresh with white flowers and nice depth. I enjoyed with griddled seafood at the brilliant Butley Oysterage in Orford, Suffolk (Ocado, Broadway Wine Co, from £20.50.)

Adnams/Sopla Poniente 7 year-old Fino, Montilla-Moriles – this is (technically illegally) labelled as a sherry, though it’s from the little-known Denominación of Montilla-Moriles, south of Córdoba and well to the east of the sherry country. It’s a very similar style to fino sherry, though made with Pedro Ximénez grapes, which are normally used to produce intensely sweet wines both in sherry and Montilla-Moriles. And yes, I only bought it because it’s obscure and I’m a sherry nut. But it’s pale, crisp and bone dry with a pleasing tang (Adnams, £9.99/50cl.)