I am a cider drinker (again)

The rise of British craft cider is enough to tempt even a relapsed Westcountry drinker like me back to the stuff. Plus: what I've been drinking this week... in Abergavenny

Adolescence can be so cruel. Especially in Devon, where I’m from, it usually involves an alcoholic baptism of fire with the local scrumpy. But while this doesn’t seem to impair most Westcountry people’s later enjoyment of cider (what Americans call “hard cider”), my first ever experience of drunkenness on it, aged about 14, put me off the drink for many decades. It was my loss.

Then at last weekend’s Abergavenny Food Festival, I tasted Tom Tibbits’s and Lydia Crimp’s Artistraw ciders from Herefordshire. It was something of a revelation. Their “Flock” cider is dry and fine, made from several apple varieties from a 90 year-old orchard. Their “Bisquet” comes solely from the apple of that name, slightly sweeter but very well balanced. It has 14 grammes/litre of residual sugar but tastes far drier than would a wine with that much – because, Tibbits thinks, of the balancing tartness of the apples’ malic acid. Then there was their perry, “Grayson” (see what they did there?), again a fine glass that set me thinking about what food it would pair with.

In truth, I’ve occasionally enjoyed cider on holiday in Brittany, where it is – of course – taken far more seriously than it is here. Cider is celebrated with even greater pride as the local drink in Normandy, and in Spain’s northern Asturias region too. At one of the most memorable meals of my life, in Nacho Manzano’s two-Michelin-star Casa Marcial in the Asturias, the sommelier served a tasting course paired with a local cider. The Asturian version is almost still, the locals’ answer to which is to pour it from as great a height as possible, bottle aloft and glass held low, in order to create bubbles in the couple of inches of liquid in the glass. This can make for a very slow drinking session.

Yet France and Spain are, respectively, the world’s second and third-biggest makers of cider – after the UK, which accounts for up to 45 per cent of global production. Despite this, while we make a lot of cider, we haven’t taken it seriously as a drink until relatively recently.

I’d like to think that cider’s renaissance has been held back by the strong thread of anti-Westcountry prejudice that still runs through British culture. Think I’m joking? We’ve got people with London, Geordie, Brummie, Northern, Scots and Irish accents all over the media – but the idea of a newsreader, announcer or game show host with a Devon burr? It’s literally unimaginable: people would say they sounded like yokels, and would feel free to take the piss in a way they wouldn’t dream of these days for other accents. When it comes to regional inclusion, the sad truth is that the British media is still with the visiting football fans at Exeter City singing, “Oi can’t read and oi can’t write, but that don’t really matter/Cos I come from the Westcountry and oi can drive a tractor.” They’m tossers, as some would say locally.

Yet even as a Devonian, I would have to concede that in fact the main thing holding back British cider was that most of it was pretty awful. And I don’t mean the stuff that you could still buy from farms in the late 70s that came in plastic gallon jugs with a greenish tinge and bits floating in it. In the 70s and 80s, cider production became dominated by a small group of companies churning out anonymous fizz: Taunton Cider (Diamond White), Showerings (Gaymers – now defunct) and by far the largest, Bulmers.

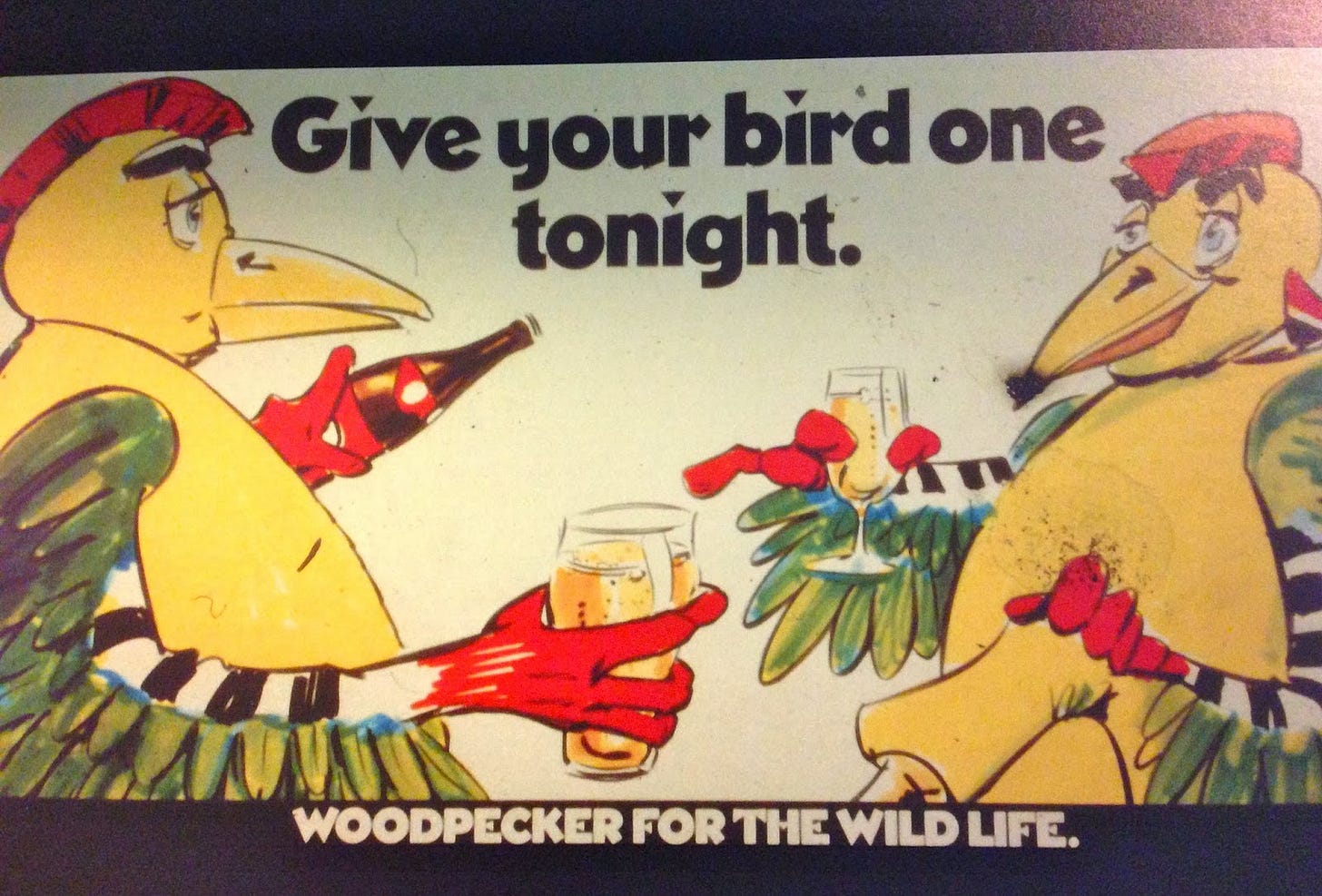

It was the latter, from Herefordshire, that launched Strongbow in 1960 ("the strong cider for men". Or if you preferred your cider sweeter, you could opt for the company’s Woodpecker brand (“Pull a bird tonight” – ah, the Britain of those “innocent” days of the 1970s.) Bulmers has been owned by Heineken since 2008; Strongbow is today by far the biggest cider brand, accounting for nearly a third of the UK market. British cider sales also got a big boost from the success of the equally gassy and commercial Magners Irish cider, launched here in 2005.

Yet a 2022 National Trust survey suggested that English and Welsh orchards had shrunk by over 80 per cent since 1900. The destruction continues, partly because cider is now declining in popularity in the UK – the National Association of Cider Makers says that consumption is down by a third in the last decade – and partly because industrial producers often prefer to make it from apple concentrate, which can be imported from Turkey and elsewhere. Legally, cider in the UK only has to contain 30 per cent apple juice.

It was this sort of bastardisation that first led to the emergence of craft ciders from the 1980s, much like the resurgence of real ale a decade earlier – albeit led then by just a handful of small producers. It took time, but over the past 20 years, craft cider’s emergence has been powered by the growing market for local and more sustainably produced products.

There are parallels with the natural wine movement. Craft cider makers reject the industrial producers’ use of concentrate, commercial yeasts and fast fermentation. Many avoid adding sugar, water, or – again like natural wine makers – sulphites as preservatives.

Instead they use natural yeasts – ones present in the orchard on the skins of the fruit, just as in a vineyard (though Somerset’s The Newt uses commercial wine yeast). Craft cider makers carefully select apples from the hundreds of native varieties available, and where possible from old and sustainably managed orchards. I was also intrigued by some of the fruit ciders available, such as SeaCider’s rhubarb-infused one, a bit sweet for me but with a pure fruit flavour, or Starvecrow’s cherry-infused cider in a Belgian kriek style.

“The big problem with cider is that it’s easy to make, but difficult to make well, because of the long ferment,” says Tibbits. That gives plenty of time for spoilage: he says, “oxygen is the greatest killer of cider and quickly spoils it.”

This is because traditional cider makers employ slow fermentation and maturation: fermentation takes four to eight months, plus anywhere from six months to over a year for the cider to mature. Some producers also use keeving, a complex traditional process where they allow a gel of pectin and yeast to form over the cider, removing nutrients so that fermentation stops before the fruit sugars have fermented out, leaving a naturally sweeter cider with lower alcohol. Many craft producers then use wood barrels to condition their cider, sometimes ones used previously for whisky or rum.

While the mass cider market may be shrinking, the number of small producers has increased rapidly over the past 15 years. This has created an excitingly diverse cider scene. “Cider’s in that weird place now,” says Chris Williams of Borough Market’s London Cider House. “Old-school cider drinkers stick to the [draught] still stuff, others want to drink it with food and cheese. You’ve got fine cider in 75cl wine bottles, from single apple varieties and so on, and easier-drinking ones on draught and in 500ml cans.”

Craft cider now makes up around a quarter of the cider sold in the UK. “A lot more people are intrigued by cider now – people have more knowledge” says Jess Driver, Assistant Manager at London Bridge’s The Miller, a pub with a good selection of draught craft ciders. The Miller now hosts a cider festival every July featuring over 100 ciders and perries.

Tibbits seems unsure of how big a thing craft cider might become. “A lot of people decide they don’t like cider because they had too much as a teenager or had a bad experience [with poorly made cider],” he says. That’s true: but I stand as living proof of fine cider’s ability to win back British drinkers. I think it has an exciting future.

Six craft ciders to try

Artistraw Flock 2023 – Artistraw’s driest cider, this is made from hand-picked, unsprayed Chisel Jersey, Bisquet, Binet Rouge and Kingston Black apples. It’s unfiltered, naturally sparkling via the Champagne method but hand-disgorged (a process unknown now in Champagne, where even artisanal bottling is mechanised.) Orange notes, fine and long.

Find & Foster Downstream 2022 – another cider made using the Champagne method, this is from Devon and stronger, at eight per cent alcohol. Crisp, fine and dry: the producer suggests pairing with seafood.

New Forest Cidre Bouché – made in Hampshire, this is a keeved cider in a very French style, slightly sweeter but still nicely balanced. Wonderfully refreshing.

Pilton “In touch” – this Somerset producer specialises in keeved ciders like this one, which is gently medium-sweet and just 4.5 per cent alcohol. What makes it very different is its use of Pinot Noir and Bacchus grape skins, added to the fermenting cider for six days. After maturing for six months, that batch is then blended with new-season keeved cider. Intriguing and delicious, with what I can only describe as a natural wine character (in a good way). Available in 75cl bottles and on draught.

Oliver’s Modern Cider – blended, fruity and medium dry, a nice, easy-drinking cider from Herefordshire. This was produced in collaboration with the Tate Modern to celebrate the gallery’s 25th anniversary this year. Available on draught and in cans.

Severn Cider Medium Sparkling – this Gloucestershire cider is actually fairly dry with an edge of sweetness, fruity and full bodied, with 5.8 per cent alcohol. Available in 330ml bottles and on draught.

Look out for my new book with Jane Masters MW, Rooted in Change: The Stories Behind Sustainable Wine – out 1 October from the Academie du Vin Library. Yes - next week!

What I’ve been drinking this week

In Abergavenny last weekend, I stopped off a couple of times at my friend Lloyd Beedell’s amazing wine shop and bar, Chester’s. He has a really impressive range of interesting wines and also a very cosy space to drink them (there’s a nice garden too, except it was raining when I went.) Of the dozen or so wines that were open to order by the glass, I loved the following reds.

Arpepe Nebbiolo 2023, Rosso di Valtellina – organically produced Nebbiolo from this alpine area, a corner of Italy sticking into Switzerland. Fragrant with bright fruit, elegant and mineral – lovely Nebbiolo (The Wine Society, Cork and Cask, Middle Lane Market, from £32.50.)

Matthieu Barret, “No Wine’s Land” 2022, Côtes du Rhône – Matthieu Barret is owner of biodynamically farmed Domaine du Coulet, a respected Cornas estate: I’m not sure if the grapes for this wine are from a declassified patch of Cornas or somewhere else. Either way, this is pure, classic northern-Rhône Syrah: deep, dark brambly fruit and minerality with a touch of graphite, so complex and long (Gourmet Hunters, Shelved Wine, Shrine to the Vine, from £27.68.)

Vino pH Pinot Noir 2022, Ceres Plateau – one of the most serious South African Pinot Noirs I’ve tasted, from a part of the Swartland region that I hadn’t heard of. Bright red fruit, earthy, elegant – very classy (Chester’s, £35. Lay & Wheeler have the 2021.)

Transparency declaration: Lloyd wouldn’t let me pay for some of my drinks, even though I tried to. I tasted cider at The Miller and London Cider House as a guest.

I want some cider now.

I thought I knew about proper scrumpy from some of the lethal pints I drank in Pompey pubs in the early 80s, but I've never come close to a 'greenish tinge with bits floating in it'!

A regular order in my late teens was a pint of snakebite and black (lager/cider not scrumpy/blackcurrant cordial) and sometimes with a shot of pernod added which I seem to remember we called a witch's tit but I see from Google that is an entirely different drink.

There used to be a very good Indian restaurant in Brighton in the 90s called the Black Chipati run by Steve Funnell (an early example of posh white boy goes back-packing and comes home and opens a restaurant inspired by his travels. It was the Kricket of its day) and he was very passionate about French cider but I think it was Normandy and not Brittany. It was probably the only time I've had properly made cider.

I've got a bottle of cheap stuff in the fridge but it's to cook with and not to drink. Maybe I should investigate what's out there now, it just never really occurs to me to drink cider, probably because of those early experiences with it as purely an intoxication engine.